This piece is one in a series that delves further into the leading themes emerging from this year’s iteration of our flagship research project, Charting Disruption.

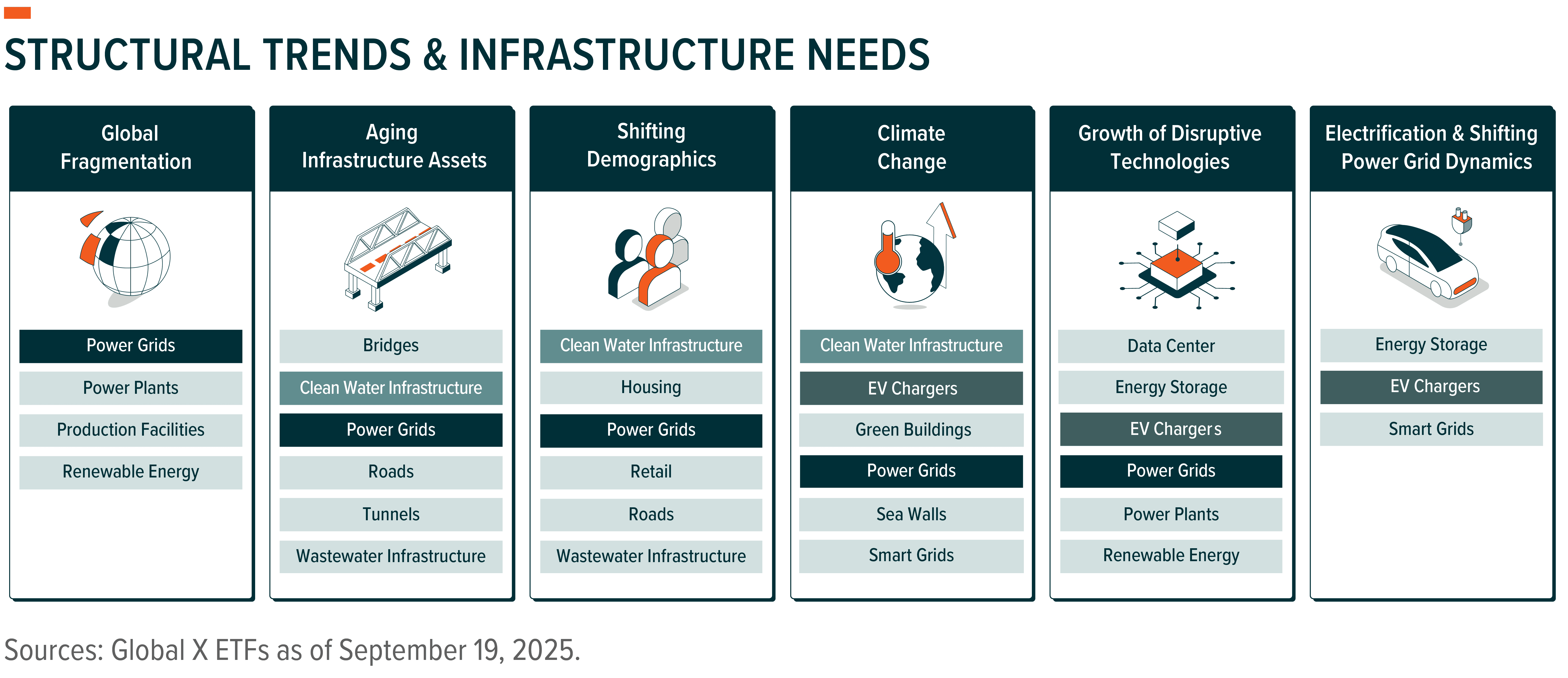

Infrastructure development opportunities are expanding globally due to several powerful structural tailwinds. For example, growing global fragmentation has increased the focus on domestic power generation and manufacturing, creating the need for new power-grid infrastructure and production facilities. Aging infrastructure assets are a challenge for developed economies, requiring repairs or replacements to critical networks. Emerging markets need new infrastructure to support larger, more urban populations. Simultaneously, the adoption of disruptive technologies such as AI, electric vehicles, and renewable energy require a massive buildout of support infrastructure, such as data centers.

Going into 2026, we expect that these dynamics to create sizable opportunities for companies providing construction materials, equipment, and services around the world.

Key Takeaways

- Infrastructure development is central to several global structural tailwinds and could require $106 trillion in investments through 2040.1

- The United States remains a leading market for infrastructure upgrades, with the reshoring of strategic industries strengthening long-term tailwinds.

- Aging infrastructure assets are likely to continue to create new infrastructure opportunities globally, including in the United States where many infrastructure asset segments are in poor condition.2

Massive Infrastructure Investment Needed as Global Demands Rise

Infrastructure is at the center of nearly every major structural shift transforming the global economy. AI, for example, depends heavily on how quickly data centers and power grid infrastructure can be built. Widespread adoption of EVs, for its part, requires charging systems and supportive electrical grid infrastructure. Meanwhile, rising trade tensions have countries racing to expand domestic manufacturing for strategic technologies, such as AI chips and EV batteries.

Additionally, supporting larger, more urban populations while mitigating impacts from climate change requires a staggering amount of infrastructure, such as modernized power grids, clean water infrastructure, and residential buildings. It is estimated that roughly half of the buildings that will need to exist globally by 2050 have yet to be constructed.3

Through 2040, investments totaling $106 trillion may be needed to meet the world’s infrastructure needs.4 Transport and logistics infrastructure have the highest projected investment requirements at $36 trillion. Energy and power infrastructure require an estimated $23 trillion, while digital infrastructure, such as data centers, could require nearly $20 trillion.5 Social infrastructure, including schools, healthcare facilities, and housing, as well as waste and water, agriculture, and defense infrastructure, could also require trillions in investments. 6

Global Fragmentation Creates New Development Opportunities for U.S. Manufacturing Facilities

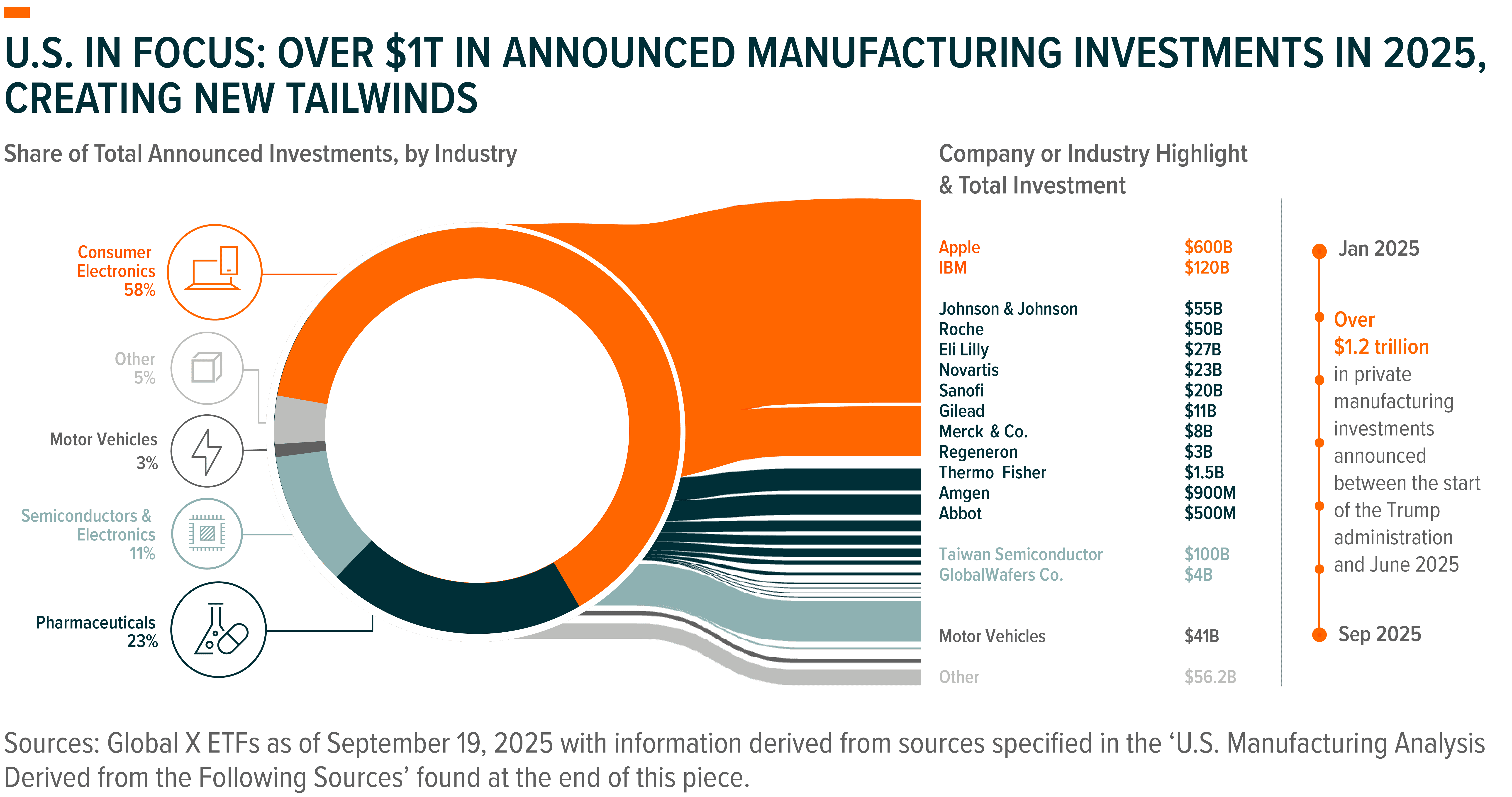

The boost for infrastructure development from rising trade fragmentation is particularly evident in the United States. In just the first eight months of the second Trump administration, companies announced nearly $1.25 trillion in investments to expand their U.S. manufacturing footprints.7 Key drivers of this trend are rising geopolitical tensions and shifting federal policies, particularly the implementation of the administration’s extensive tariff scheme.

While the announcements span a variety of industries, much of the planning pipeline is concentrated in strategic areas. Consumer electronics leads with more than $700 billion in announced U.S. investments, although the category is heavily concentrated in just two companies.8 Pharmaceutical manufacturing investments total $290 billion across 18 announcements from both domestic and international drugmakers. Semiconductor manufacturers account for 11% of announced investments, with plans to spend $134 billion on top of the $300 billion announced prior to 2025.9,10

As of July 2025, construction spending on manufacturing accounted for just under 15% of total private construction spending in the United States, a 2.5x increase from January 2021.11,12 We believe the flurry of investments over 2025 could push manufacturing’s share of construction spending higher over the medium to long term.

Aging Infrastructure Is a Common Concern for Developed Economies, Including the United States

Decades-old assets can slow economic growth and hamper the adoption of disruptive technologies. For example, even though electricity can be viewed as essential to economic and social progress, power grids are frequently underfunded and outdated.13 In Japan, over two-thirds of transmission infrastructure is at least 20 years old. Nearly half of all transmission infrastructure in the United States and over 40% of assets in the European Union are also at least two decades old.14

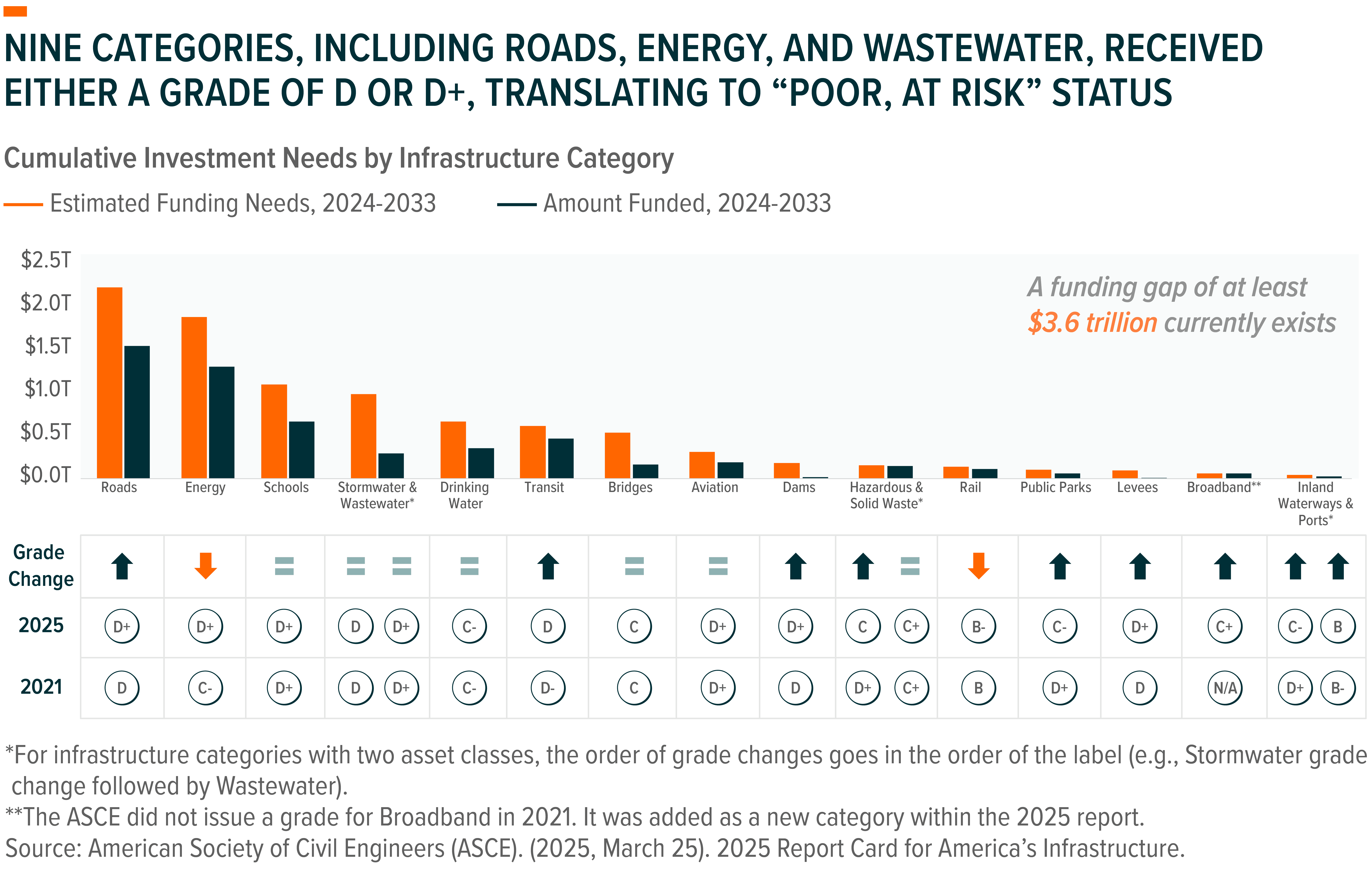

For the United States, inadequate infrastructure conditions extend well beyond the power grid. Despite increased funding over the past four years, the American Society of Civil Engineers only improved the country’s overall infrastructure grade from a C- in 2021 to a C in 2025.15 Half of the assessed categories received either a D or D+, translating to “Poor, At Risk” status. This means that these nationwide systems are in fair to poor condition and “mostly below standard, with many elements approaching the end of their service life.”16

Improving the quality of infrastructure in the United States alone could require $9.1 trillion in investments between 2024 and 2033. Over $5 trillion in funding has been allocated, meaning that a multi-trillion-dollar investment gap still needs to be filled by additional public and private spending.17 Similarly, the European Union faces a $2 trillion infrastructure investment gap when considering expected infrastructure development needs and announced funding through 2040.18

Conclusion: Infrastructure Renaissance Could Emerge from Surging Public and Private Investment

Global infrastructure development is increasingly pivotal to the economies of the future. The adoption of disruptive technologies such as AI, the reshoring of strategic supply chains, and the growth of urban populations all depend on how quickly supportive infrastructure can be built. As these demands rise, so too could opportunities for companies – and investors – across the infrastructure development value chain.

For additional insights, please view our full report, Charting Disruption: Outlook for 2026 and Beyond.